David Cloud provides an example of ecclesial deism when in "The Church Fathers, A Door To Rome," he writes:

"The fact is that the "early Fathers" were mostly heretics!"

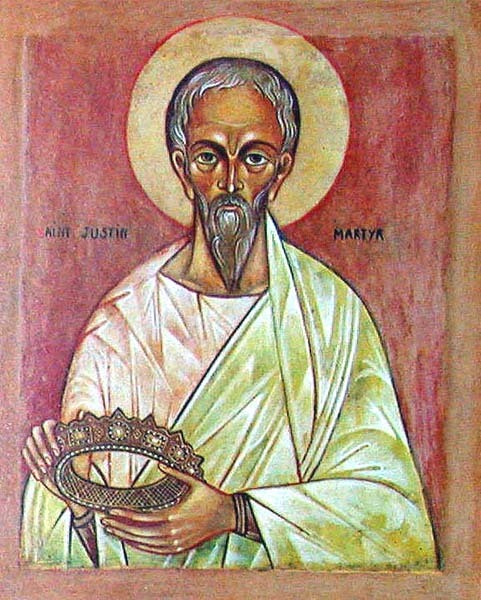

At what point does one's own disagreement with the early Church Fathers become evidence against one's own position, rather than an indication that the early Church Fathers were "mostly heretics"? St. Justin Martyr, born around the time that the Apostle John died, describes a Catholic mass in the video below, explaining in his Apology that they had received their belief and practice from the Apostles. St. Justin's testimony counts far more than does the testimony of a contemporary twenty-first century figure, precisely because of St. Justin's closer proximity to the Apostles. So claiming that the early Fathers were "mostly heretics" is in that respect self-refuting. But it is forthright and correct in its recognition of the distinctively Catholic nature of the early Church Fathers.