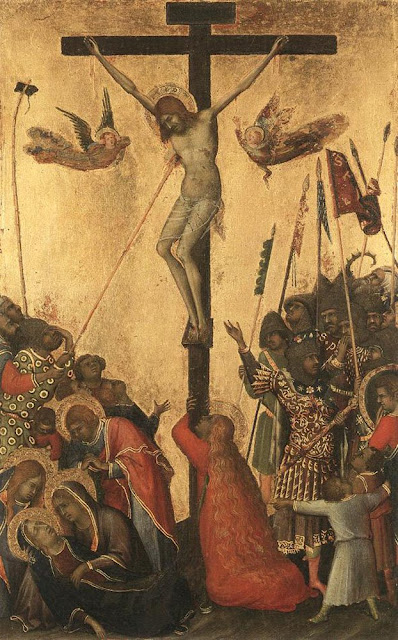

The cartoon above by John Dearstyne can be found in Michael Horton's Putting Amazing Back Into Grace (1991), and it represents the [popular] Reformed conception of justification. According to this conception of justification, God, on account of Christ, treats us as though we are righteous, even though in actuality we remain unrighteous. The "good news" according to this conception, is that because of Christ's work on the cross, we are going to heaven, in spite of our remaining unrighteous, if we trust in Christ's work to get us to heaven. (I discussed the problem with this position in greater detail here.)

The common question that arises is this: If Christ's work was sufficient, then what room is left for us to contribute anything to our final justification? The dilemma looks like this: Either part of our final justification is from ourselves, in which case Christ's work was not sufficient for our final justification, or Christ's work was sufficient for our final justification, in which case there is no room or space left for us to contribute to our final justification. Or again: Either all our righteousness is Christ's, in which case we contributed nothing, or our righteousness is some fraction of Christ's righteousness and our own righteousness (e.g. 50/50, or 70/30, etc.).

I want to point out here that this is a false dilemma, because it implicitly assumes the truth of monocausalism. (See my previous post titled "Monocausalism, Salvation and Reconciliation".) How so? Implicit within the dilemma is the notion that if our doing a good work is a righteous act, then the righteousness of that righteous act is not merely "our own" but also "our own and not Christ's". (Notice the monocaualism.) Or, putting it the other way around, since, given monocausalism, a righteous act done by us would be done "only by us and not also by Christ", then since all our righteousness comes from and through Christ, it follows that we cannot do a righteous act. Hence, one of the errors of Martin Luther condemned in the Papal Bull "Exsurge Domine" (June 15, 1520) is this: "In every good work the just man sins." John Calvin similarly claimed that "all human works, if judged according to their own worth, are nothing but filth [iniquinamenta] and defilement [sordes]." (Institutes 3.12.4)

Monocausalism is the philosophical assumption in play behind the treatment of our justification [initial and final] as a mere imputation, and not an infusion. It makes righteousness out to be a quantifiable entity, like a pie composed of, say, eight pieces. If n pieces of the pie were contributed by me, then God could only contribute (8-n) pieces. The more I contribute, the more it detracts from God's contribution, and hence the more I contribute, the more it detracts from God's glory and from my dependence on God for my salvation. That account is based on the mistaken notion that righteousness and glory are quantifiable entities, comparable to something like a pie, and that God's contribution and my contribution are made at the same ontological level. That is why from the point of view of the monocausalist there is no causal room for mutual contribution without competition [e.g. if the whole is 8, and my contribution is n, then God's contribution can be no more than (8-n)].

But righteousness and glory and love are not like that. They are, ultimately, divine attributes; they do not compete for space in God. God is not part love, part righteousness, part glory, etc. Similarly, when God gives love, He does not lose any love. When God gives glory, He does not lose glory. When God gives righteousness, He does not lose righteousness. Similarly, when we love, we do so because He first loved us. Our love is genuine, even though it has its ultimate source in God. To think of love as either only from us, or only from God, is to fail to understand the relation between the Creator and the creature, between first and second causes. It fails to conceive of or imagine the possibility of concurrence.

Everything we have, save sin, is from God. And yet God has given us real powers, real freedom and choice, so that our actions are truly our own. We are actual agents, not robots. For that reason, even though all our righteousness is from God through Christ, nevertheless that righteousness is also (by grace) truly ours, on the inside, by infusion. Our hearts are transformed; we are truly and actually made righteous. That's the good news! We (as real agents, not robots or zombies) actually love God and are made truly righteous, by the grace of God, through faith in Christ, and this grace, faith, righteousness and love are all His gifts to us. They are all 100% divine gift, and yet they are truly and actually ours.

Consider this paragraph from the sixth session of the Council of Trent:

Thus, neither is our own justice established as our own from ourselves, nor is the justice of God ignored or repudiated, for that justice which is called ours, because we are justified by its inherence in us, that same is [the justice] of God, because it is infused into us by God through the merit of Christ. (chapter 16)

Notice here that the justice (i.e. righteousness) of Christ is also actually and truly ours. It is truly Christ's, and truly ours, without contradiction and without confusion or admixture. It is not part Christ's and part ours. It is 100% Christ's, and 100% ours, just as Jesus Himself is 100% God and 100% human, without contradiction or confusion or admixture.

The "mere imputation" view depicted in the cartoon above does not truly *unite* Christ's righteousness to us. It treats Christ's righteousness as remaining extrinsic to us. (That's why the guy in the cartoon is hiding; he is using Christ as his fig leaf, rather than having, as St. Paul said, "Christ in you". Col 1:27). That is because given monocausalism, the only two alternatives for us to be righteous are: (1) for Christ Himself (and Christ alone) to act in us, taking over our will and making our choices for us and in that way turning us into puppets or "possessed" beings, having no genuine causal agency of our own, or (2) we act apart from Christ, in which case if our deeds were righteous then some sort of Pelagianism would be true. To avoid both of those possibilities, monocausalism must settle for "mere imputation", an extrinsic union wherein on account of Christ's righteousness, God the Father treats us as if we were righteous even though we are actually unrighteous, and the problem of our actual unrighteousness is not addressed until we die. (According to Reformed theology we do in theory grow in sanctification over the course of our life after we come to believe the gospel, but nevertheless, even up to and including the last moment of our life, we are still like the guy in the cartoon above: simul iustus et peccator (simultaneously justified and sinner); we are still unrighteous, and all our 'righteousness' is as worthless as filthy rags.

To understand the gospel as something by which we are made actually and truly righteous (and not merely declared to be righteous while remaining in fact unrighteous), we need to consider what exactly the fall did to man, and then in light of that, reflect on what it means to be saved. See my "Prolegomena to the gospel". But my purpose in this post is only to point out the philosophical assumption (of monocausalism) that is at work in the background of the more commonly known Reformed conception of justification, particularly in the claim that if we contribute to our final justification, then Christ's work was not sufficient, and *part* of our righteousness is then coming from [ourselves and not from Christ].