I have no desire to turn this blog into a political forum, so I wasn't going to post anything here having to do with politics. But I believe that Protestants and Catholics can find much common ground in the moral questions that face us as citizens when determining which candidates should receive our vote. The more we recognize this common ground, the more we see each other as [separated] brothers and sisters, and the more we yearn for full communion.

The opening line of that ancient text known as the Didache says the following:

"There are two ways, one of life and one of death; but a great difference between the two ways."

Those two ways remain before us today. Pope John Paul II referred to them as the "culture of life" and the "culture of death". As Christians we must seek to bring about within our nation the culture of life, and stand firm in opposition to the culture of death.

What does the Church teach us about the selection of candidates for political office? The issues have to be weighed according to their importance. Which issues are the most important? That is, which issues are the ones upon which the very continuation of society stands or falls? I'm not talking about our contemporary 'way of life'; I mean society itself. The most fundamentally essential issues are the issues of life and family, because these two issues are at the core (i.e. the intrinsic heart) of the possibility of society. (In addition, see here.)

There are outside threats to a society, but the most dangerous threats are the ones that destroy it from the inside, just as the most dangerous threats to an individual person are not the external threats to his body, but the corruption of his soul. A healthy body and a corrupt soul is a far worse condition than an ailing body and a virtuous soul. And the same applies to a society. The economy is a secondary priority, because it concerns secondary goods having to do mostly with external possessions and bodily goods. As a society we can survive with less material wealth than we presently have, so long as the right to life and the institution of the family are respected and preserved. But if the right to life and the institution of the family are lost sight of or practically eliminated, we cannot survive at all, nor can we sustain an economy. Similarly, the military is a secondary priority, precisely because it protects us from an external threat. And the environment likewise is a matter of secondary importance for the very same reason. It concerns our bodily well-being. And the same is true of health care -- it concerns bodily goods. And the same goes for foreign policy.

If we do not recognize the absolutely essential role that public recognition, respect and protection of the right to life and the institution of the family play in the preservation of a society, then issues of life and family will seem like merely private non-essentials, and all these other issues will seem equally important or maybe even more important. But respect for life and the family are the internal preconditions for the possibility of society, and as such are sine qua non. All the other issues ultimately draw their importance from the intrinsic value of human life made in the image of God, and the flourishing of human life in the family as its natural and most basic social institution.

In certain respects we as a people are losing sight of the intrinsic value and dignity of human life, and the intrinsic right to life. Take as an example our present treatment of children with Down syndrome. The number of children with Down syndrome is rapidly falling, because now in the US ninety percent of babies whose Down syndrome is detected in utero are aborted; in Norway 84% of all Down syndrome children are aborted. In Spain the number is 95%. Contrast that attitude with that of this man, who gave his life on September 8. (See here for an update.) We can keep belittling the 'slippery slope fallacy', but the fact is that we are rapidly (from an historical point of view) descending that slope. And if we don't stand up and stop it, God won't have to send any fire and brimstone, because we will have destroyed ourselves and the hope of future generations. We face before us the real possibility of the moral and social equivalent of the runaway greenhouse effect.

That is why the person most opposed to protecting the lives of infants is ipso facto the least qualified person to lead our country. How can a man for whom determining when a baby has human rights is "above [his] pay grade" be entrusted with protecting and upholding those very rights? That would be like entrusting one's children to a babysitter who says that determining the age of sexual consent is above his pay grade. We would not hesitate to direct such a job-seeker to a different line of work. How much more then, should we firmly insist that one entrusted with the government of our country's 300 million citizens at least understand and be committed to upholding and defending the basic human right to life from conception to natural death.

As Christians, our voting should not be just like that of the world, having the very same priorities and values; it should reflect the divine perspective found already in the first chapters of Genesis. There we see that humans are made in the image of God. Therefore we must stand up to defend human life, especially the innocent and defenseless. Likewise, in Genesis we see that marriage and family were established by God, as the fundamental basis for all of human society. That is why we must require of our governing leaders formal recognition and defense of the institution of the family. In short, to qualify for public office, candidates must recognize the foundational primacy of the public recognition and respect for the intrinsic sanctity of human life and the natural institution of marriage.

The objection to the notion of a 'single-issue voter' is based on the assumption that no single issue or single category of issues is so much more important than the rest. But that is not a safe assumption, as is made clear if the candidate supported child pornography, or wanted to bring back slavery, or annihilate a particular race of persons. We should seek to see things as they actually are, according to their actual importance. And that is why, according to the Church, we need to see the issues of life and family as the two most important issues that stand before us. Abortion has become such a commonplace event and a throwaway term that many of us have become numb to what it actually is, the gratuitous killing of innocent and defenseless human beings at the rate of 1,300,000 per year in the US. If Abel's blood cried out from the ground, what must be the sound of all this innocent blood?

The Church has always condemned abortion as homicide. And one political candidate has promised to pass legislation that would result in an additional 125,000 abortions per year. His party risks becoming a "party of death". There should be no downplaying of this issue on the part of Christians. It should be well known that from the Christian point of view (whether Protestant or Catholic), anyone who does not oppose abortion does not qualify to be considered for public office, because he or she has failed to perceive the most fundamental value, foundational to all the others that a public servant must defend, namely, the intrinsic value of human life. My brothers and sisters, let us stand together and choose the way of life, not the way of death.

"Let unity, the greatest good of all goods, be your preoccupation." - St. Ignatius of Antioch (Letter to St. Polycarp)

Tuesday, September 30, 2008

Monday, September 29, 2008

So much for sola over solo

(For an explanation of the sola vs. solo distinction, see here.)

In May of this year I wrote a post titled "Denominational Renewal", about the conference by that name that had taken place here in St. Louis in February, and which I attended. Presently, there is an ongoing five-week discussion about that conference over at "Common Grounds Online". What got my attention, however, were Bob Mattes's recent comments on Jeremy Jones's talk given at the conference. Bob described Jeremy's proposal in this way:

Bob disagrees with Jeremy's position. Bob responds a few paragraphs later with this critical, noteworthy paragraph. He writes:

When I have pointed out that the Protestant position reduces in principle to biblicism (see, for example, here and here), the reply I typically receive is that I have failed to appreciate fully the distinction between sola scriptura and solo scriptura. Sola scriptura, Keith Mathison tells us, embraces the creeds and the teachings of the Church fathers. But then when people (like Jeremy) start referring to that catholic tradition that would be included in sola scriptura but not in solo scriptura, they're told that the Reformers built on Scripture alone, because the Church that Christ founded had long been trampled into oblivion.

Of course the gates of hell cannot prevail against the Church. Therefore confessional Protestants must posit the existence during that long period of apostasy of at least one person in every generation who believed in justification by faith alone. But since in Protestantism the Church Christ founded is really just the set of all the elect, there is no compelling reason even to posit that anyone from the time of the death of the last Apostle to Luther heard the gospel and was saved, because the only way for hell to prevail over the Church would be to prevent the set of all the elect from attaining the number of members God intends it to have. And that's impossible. So a long period of time without any elect persons on earth is fully compatible with Christ's promise not to allow the gates of hell to prevail against the Church, if the Church is merely the set of all the elect. But just to be safe (perhaps because of vestiges of the notion of a visible Church), Protestants still want to posit a priori that some proto-Lutherans were alive during the long apostasy, even if they have no evidence that such persons existed.

At the time Luther came along, how long had the apostasy been going on? Alister McGrath has pointed out that the notion of justification by "faith alone" was unknown from the time of St. Paul to the Reformation, calling it a "genuine theological novum". According to McGrath, the Council of Trent "maintained the medieval tradition, stretching back to Augustine, which saw justification as comprising both an event and a process -- the event of being declared to be righteous through the work of Christ and the process of being made righteous through the internal work of the Holy Spirit." (Reformation Thought, 1993, p. 115) McGrath is very clear that Luther's notion of justification by faith alone is not that of St. Augustine. Trent's position followed that of St. Augustine, not Luther. B.B. Warfield likewise, condemns the Council of Orange (529 AD) as "semi-semi-Pelagianism", as I pointed out here. So for these Protestants the great apostasy was at least a thousand years in length.

The Protestant argument goes like this.

(1) Clearly Luther was right about justification.

Therefore,

(2) Everyone who preceeded Luther and held a view of justification contrary to that of Luther was wrong.

(3) But everyone [so far as we can tell from history] at least from Augustine on (and perhaps even back to the first century) held a view of justification contrary to that of Luther.

(4) Justification [as imputation alone] by faith alone is the heart of the gospel, the doctrine on which the Church stands or falls.

Therefore

(5) The Church was apostate from the time of Augustine (or even all the way back to the first century) until Luther.

But one man's modus ponens is another's modus tollens. In other words, how much ecclesial deism and ecclesial docetism does it take to call into question the perspicuity assumption underlying premise (1)? At what point does one say, "Wait a second; maybe Luther's interpretation isn't right"? This is the heart of the paradigm shift I have spoken of here.

I talked to a Reformed Protestant recently who said that returning to the Catholic Church would require giving up all the "theological development" (his terms) within Protestantism from the time of Luther and Calvin to the present. Whether that is true or not, Protestants like Mattes seem to have no problem giving up the first 1000 - 1500 years of theological development. If that is the case, then it is not just 'development' per se that such Protestants are adhering to, but rather 'the development I approve of'. And that seems to be the individualism of biblicism, precisely why there is no principled difference with respect to individualism between sola scriptura and solo scriptura.

Sean Michael Lucas, in commenting on Jeremy's talk writes the following:

This is the same Irenaeus who around 180 AD wrote:

"We do put to confusion all those who ... assemble in unauthorized meetings; [we do this, I say,] by indicating that tradition derived from the apostles, of the very great, the very ancient, and universally known Church founded and organized at Rome by the two most glorious apostles, Peter and Paul; as also [by pointing out] the faith preached to men, which comes down to our time by means of the successions of the bishops. For it is a matter of necessity that every Church should agree with this Church [of Rome], on account of its preeminent authority, that is, the faithful everywhere, inasmuch as the apostolical tradition has been preserved continuously by those [faithful men] who exist everywhere." (Against Heresies 3.3.2)

This is the same Tertullian who around 200 AD wrote:

"Was anything withheld from the knowledge of Peter, who is called the rock on which the church should be built,' who also obtained the keys of the kingdom of heaven, with the power of loosing and binding in heaven and on earth? Moreover, if Peter was reproached [by Paul] because, after having lived with the gentiles, he later separated himself from their company out of respect for persons, the fault certainly was one of procedure and not of doctrine." (Prescription Against the Heretics, 22)

Sean wants unoriginality. But, according to McGrath, originality is precisely what Luther offers. Luther's originality doesn't count as originality, however, because it matches (sufficiently) Sean's interpretation of Scripture. Whatever the fathers say that doesn't match the Protestant's interpretation of Scripture (e.g. claims about Peter being the rock, Rome having the primacy, bishops, apostolic succession, Mary as "Mother of God", prayers for the dead, prayers to saints, Eucharist as sacrifice, etc.) is ipso facto an originality and can thus be dismissed. Originality, therefore, means by definition, any claim or teaching by any post-Apostolic writer over the last 2000 years whose claim goes beyond what is allowed by the Protestant's own interpretation of Scripture. Unoriginality, likewise, means by definition, any claim or teaching by any post-Apostolic writer over the last 2000 years whose claim fits with one's own interpretation of Scripture (and/or the particular confessions one has adopted as representing what one believes to be the best interpretation of Scripture).

We find here that in sola scriptura as a practice, the content of the authoritative extra-biblical tradition that stands along with (but subordinate to) Scripture is by definition whatever can be found in the last twenty (but especially the first few) centuries of Church history that agrees with the particular Protestant interpretation in question. Solo scriptura is doing all the work to determine what gets included in or excluded from what is presented as the sola scriptura package. Sola is the advertisement photo; solo is what's inside the package. The method being used is not that of reading-Church-history-forward to see how the Church grows organically, but rather, starting from Scripture as read through Protestant lenses, and then reading back into Church history, to try to find whatever is there that agrees with one's own interpretation of Scripture. Any heretics throughout history could use the same method, and call their doctrine the 'apostolic' doctrine because by study and interpretation they 'derived' it from the writings of the Apostles. That methodological parallel should give any Protestant serious pause, to ask these questions: "What makes our activity of study and interpretation so much better that we're immune from heresy? And why is our ecclesial deism any better than theirs?"

Angels Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael, on this feast of Michaelmas, do battle against the rulers, against the powers, against the world forces of this darkness, against the spiritual forces of wickedness in the heavenly places, so that the full visible unity of all Christians may be restored, according to the heart of Jesus revealed in His prayer in St. John 17. In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, Amen.

In May of this year I wrote a post titled "Denominational Renewal", about the conference by that name that had taken place here in St. Louis in February, and which I attended. Presently, there is an ongoing five-week discussion about that conference over at "Common Grounds Online". What got my attention, however, were Bob Mattes's recent comments on Jeremy Jones's talk given at the conference. Bob described Jeremy's proposal in this way:

He [Jeremy] proposes to replace sectarianism with Reformed Catholicism theology. He says that we are part of the universal Catholic Church, that the enemy isn't the church down the street but the world, flesh, and the devil. ... But then he says that we need to recovery of the ecclesial identity of the original Reformed fathers, who saw themselves as a branch of Roman Catholic Church. ... Jeremy offers the illustration of a house. The foundation of the house is the Word, the 1st floor is Catholic tradition in the Roman sense. The 2nd floor has the subdivided apartments of Protestantism. TE Jones says that if you’re Protestant, you rest on top of the Roman Catholic tradition - that they mediated the Catholic faith to us. Hence, it is all one building. He claims that a Reformed Catholic identity illumens a broader historic belief, that the creeds come from RCC and the Reformers tried to reform the Roman Catholic Church, not pitch it. He says that they did not alter the core doctrines ... but reformed those they found in error within the bounds of the RCC tradition which remained substantially unaltered. ... He says that this provides a different scale of importance in our theology, so that Catholic creedal orthodoxy becomes more basic than Reformed theology. (emphasis his)

Bob disagrees with Jeremy's position. Bob responds a few paragraphs later with this critical, noteworthy paragraph. He writes:

No, the Reformers bypassed the Roman doctrines to study the Bible itself from the original languages. They pitched the sacrifice of the mass, transubstantiation, purgatory, Mariology, leadership structure, etc. They did not attempt to reform the Roman church itself in the long run, but strove to recapture the truths of, and build upon, the foundation of Christ and His Word directly. They also used the early creeds which were developed before the corruption of Rome trampled the early church into oblivion. In response to the Reformation, the Roman church anathematized the gospel at the Council of Trent. The doctrines canonized at Trent weren’t new. Rome’s long-time doctrines were simply codified there. How can one build upon such a foundation? Surely this is a foundation of sand which our Lord contrasted to the Rock of our salvation. (emphasis his)

When I have pointed out that the Protestant position reduces in principle to biblicism (see, for example, here and here), the reply I typically receive is that I have failed to appreciate fully the distinction between sola scriptura and solo scriptura. Sola scriptura, Keith Mathison tells us, embraces the creeds and the teachings of the Church fathers. But then when people (like Jeremy) start referring to that catholic tradition that would be included in sola scriptura but not in solo scriptura, they're told that the Reformers built on Scripture alone, because the Church that Christ founded had long been trampled into oblivion.

Of course the gates of hell cannot prevail against the Church. Therefore confessional Protestants must posit the existence during that long period of apostasy of at least one person in every generation who believed in justification by faith alone. But since in Protestantism the Church Christ founded is really just the set of all the elect, there is no compelling reason even to posit that anyone from the time of the death of the last Apostle to Luther heard the gospel and was saved, because the only way for hell to prevail over the Church would be to prevent the set of all the elect from attaining the number of members God intends it to have. And that's impossible. So a long period of time without any elect persons on earth is fully compatible with Christ's promise not to allow the gates of hell to prevail against the Church, if the Church is merely the set of all the elect. But just to be safe (perhaps because of vestiges of the notion of a visible Church), Protestants still want to posit a priori that some proto-Lutherans were alive during the long apostasy, even if they have no evidence that such persons existed.

At the time Luther came along, how long had the apostasy been going on? Alister McGrath has pointed out that the notion of justification by "faith alone" was unknown from the time of St. Paul to the Reformation, calling it a "genuine theological novum". According to McGrath, the Council of Trent "maintained the medieval tradition, stretching back to Augustine, which saw justification as comprising both an event and a process -- the event of being declared to be righteous through the work of Christ and the process of being made righteous through the internal work of the Holy Spirit." (Reformation Thought, 1993, p. 115) McGrath is very clear that Luther's notion of justification by faith alone is not that of St. Augustine. Trent's position followed that of St. Augustine, not Luther. B.B. Warfield likewise, condemns the Council of Orange (529 AD) as "semi-semi-Pelagianism", as I pointed out here. So for these Protestants the great apostasy was at least a thousand years in length.

The Protestant argument goes like this.

(1) Clearly Luther was right about justification.

Therefore,

(2) Everyone who preceeded Luther and held a view of justification contrary to that of Luther was wrong.

(3) But everyone [so far as we can tell from history] at least from Augustine on (and perhaps even back to the first century) held a view of justification contrary to that of Luther.

(4) Justification [as imputation alone] by faith alone is the heart of the gospel, the doctrine on which the Church stands or falls.

Therefore

(5) The Church was apostate from the time of Augustine (or even all the way back to the first century) until Luther.

But one man's modus ponens is another's modus tollens. In other words, how much ecclesial deism and ecclesial docetism does it take to call into question the perspicuity assumption underlying premise (1)? At what point does one say, "Wait a second; maybe Luther's interpretation isn't right"? This is the heart of the paradigm shift I have spoken of here.

I talked to a Reformed Protestant recently who said that returning to the Catholic Church would require giving up all the "theological development" (his terms) within Protestantism from the time of Luther and Calvin to the present. Whether that is true or not, Protestants like Mattes seem to have no problem giving up the first 1000 - 1500 years of theological development. If that is the case, then it is not just 'development' per se that such Protestants are adhering to, but rather 'the development I approve of'. And that seems to be the individualism of biblicism, precisely why there is no principled difference with respect to individualism between sola scriptura and solo scriptura.

Sean Michael Lucas, in commenting on Jeremy's talk writes the following:

... it strikes me that [Jeremy's] proposal for renewing theology holds out great hope for "creative theological thinking." And yet, if we pay attention to those witnesses of the past, like Irenaeus and Tertullian, they stressed not their creativity, but their unoriginality. For example, when Irenaeus sought true missional impact, he stressed "this kerygma and this faith the Church, although scattered over the whole world, diligently observes, as if it occupied but one house, and believes as if it had but one mind, and preaches and teaches as if it had but one mouth." Perhaps the agenda for renewing theology should not be to look for "creatively faithful, constructive theology," but for a continuing witness to "the faith once delivered to the saints" (Jude 3). (my emphasis)

This is the same Irenaeus who around 180 AD wrote:

"We do put to confusion all those who ... assemble in unauthorized meetings; [we do this, I say,] by indicating that tradition derived from the apostles, of the very great, the very ancient, and universally known Church founded and organized at Rome by the two most glorious apostles, Peter and Paul; as also [by pointing out] the faith preached to men, which comes down to our time by means of the successions of the bishops. For it is a matter of necessity that every Church should agree with this Church [of Rome], on account of its preeminent authority, that is, the faithful everywhere, inasmuch as the apostolical tradition has been preserved continuously by those [faithful men] who exist everywhere." (Against Heresies 3.3.2)

This is the same Tertullian who around 200 AD wrote:

"Was anything withheld from the knowledge of Peter, who is called the rock on which the church should be built,' who also obtained the keys of the kingdom of heaven, with the power of loosing and binding in heaven and on earth? Moreover, if Peter was reproached [by Paul] because, after having lived with the gentiles, he later separated himself from their company out of respect for persons, the fault certainly was one of procedure and not of doctrine." (Prescription Against the Heretics, 22)

Sean wants unoriginality. But, according to McGrath, originality is precisely what Luther offers. Luther's originality doesn't count as originality, however, because it matches (sufficiently) Sean's interpretation of Scripture. Whatever the fathers say that doesn't match the Protestant's interpretation of Scripture (e.g. claims about Peter being the rock, Rome having the primacy, bishops, apostolic succession, Mary as "Mother of God", prayers for the dead, prayers to saints, Eucharist as sacrifice, etc.) is ipso facto an originality and can thus be dismissed. Originality, therefore, means by definition, any claim or teaching by any post-Apostolic writer over the last 2000 years whose claim goes beyond what is allowed by the Protestant's own interpretation of Scripture. Unoriginality, likewise, means by definition, any claim or teaching by any post-Apostolic writer over the last 2000 years whose claim fits with one's own interpretation of Scripture (and/or the particular confessions one has adopted as representing what one believes to be the best interpretation of Scripture).

We find here that in sola scriptura as a practice, the content of the authoritative extra-biblical tradition that stands along with (but subordinate to) Scripture is by definition whatever can be found in the last twenty (but especially the first few) centuries of Church history that agrees with the particular Protestant interpretation in question. Solo scriptura is doing all the work to determine what gets included in or excluded from what is presented as the sola scriptura package. Sola is the advertisement photo; solo is what's inside the package. The method being used is not that of reading-Church-history-forward to see how the Church grows organically, but rather, starting from Scripture as read through Protestant lenses, and then reading back into Church history, to try to find whatever is there that agrees with one's own interpretation of Scripture. Any heretics throughout history could use the same method, and call their doctrine the 'apostolic' doctrine because by study and interpretation they 'derived' it from the writings of the Apostles. That methodological parallel should give any Protestant serious pause, to ask these questions: "What makes our activity of study and interpretation so much better that we're immune from heresy? And why is our ecclesial deism any better than theirs?"

Angels Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael, on this feast of Michaelmas, do battle against the rulers, against the powers, against the world forces of this darkness, against the spiritual forces of wickedness in the heavenly places, so that the full visible unity of all Christians may be restored, according to the heart of Jesus revealed in His prayer in St. John 17. In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, Amen.

Sunday, September 28, 2008

Love and Unity: Part 2

Part 1 is here.

In order to understand better why love seeks union with the beloved, we first need to step back and consider what love is. I am not here addressing the theological virtue of charity. Grace builds upon and perfects nature, so to understand the theological virtue of charity, we must first understand natural love. Writing about the nature of love may not seem to have anything to do with the reunion of all Christians. But it serves as the philosophical background for the argument that if we truly love one another, then we will actively be seeking unity with each other, pursuing every attempt to be reconciled and reunited. Part of what it means to obey Christ's command to love one another, I will argue, is to seek unity with each other. If we say that we love each other, but are content with being divided, then we are deceiving ourselves. A week ago Pope Benedict said, "Is it indeed possible to be in communion with the Lord if we are not in communion with each other? How can we present ourselves divided and far from each other at God's altar?" Some of what I have written in this post is more philosophical in nature and terminology, so please bear with me.

Aquinas tells us that everything by its very nature has a natural aptitude or inclination toward its natural form, that is, its natural perfection. In things that do not have knowledge, this natural aptitude is called natural appetite (appetitus naturalis). (ST I Q.19 a.1 co.) Seedlings, for example, have a natural appetite for becoming full-grown trees, even though seedlings do not themselves have knowledge of this goal. The knowledge of their goal remains in their Designer, but the natural appetite for their goal is within the seedlings.

Aquinas tells us that everything by its very nature has a natural aptitude or inclination toward its natural form, that is, its natural perfection. In things that do not have knowledge, this natural aptitude is called natural appetite (appetitus naturalis). (ST I Q.19 a.1 co.) Seedlings, for example, have a natural appetite for becoming full-grown trees, even though seedlings do not themselves have knowledge of this goal. The knowledge of their goal remains in their Designer, but the natural appetite for their goal is within the seedlings.

In addition to this natural appetite, animals and humans have something that plants do not have; we have the power to sense material things that are outside of us. Accompanying this power to sense material things is an additional appetitive power by which we can desire the things whose sensible forms we receive in our sense powers. In virtue of this appetitive power, animals and humans can desire the things that we sense insofar as we apprehend them as desirable, i.e. as suited to our natural perfection. (ST I Q.78 a.1 co.) This appetite is the sensitive appetite or "sensuality" (sensualitas). (ST I Q.81 a.1 co.)

Humans are distinguished from other animals in that we have a rational soul. This allows us to receive not just sensible forms, but also intelligible forms. In this way we are capable of understanding what a thing is, that is, its essence. But again, along with this greater power of apprehension is a greater corresponding appetitive power. This greater appetitive power is the "rational appetite", which is another term for the will. Aquinas describes this three-fold distinction in appetites in this way:

[A]ll things in their own way are inclined by appetite towards good, but in different ways. Some are inclined to good by their natural inclination, without knowledge, as plants and inanimate bodies. Such inclination towards good is called "a natural appetite." Others, again, are inclined towards good, but with some knowledge; not that they know the aspect of goodness [rationem boni], but that they apprehend some particular good; as in the sense, which knows the sweet, the white, and so on. The inclination which follows this apprehension is called "a sensitive appetite." Other things, again, have an inclination towards good, but with a knowledge whereby they perceive the aspect of goodness [boni rationem]; this belongs to the intellect. This is most perfectly inclined towards what is good; not, indeed, as if it were merely guided by another towards some particular good only, like things devoid of knowledge, nor towards some particular good only, as things which have only sensitive knowledge, but as inclined towards good in general[universale bonum]. Such inclination is termed "will." (ST I Q.59 a.1 co.)

Aquinas sums this up in his answer to the question of whether there is natural love in the angels. And here we see what appetite has to do with love. He writes:

But it is common to every nature to have some inclination; and this is its natural appetite or love. This inclination is found to exist differently in different natures; but in each according to its mode. Consequently, in the intellectual nature there is to be found a natural inclination coming from the will; in the sensitive nature, according to the sensitive appetite; but in a nature devoid of knowledge, only according to the tendency of the nature to something. (ST I Q.60 a.1 co.)

Notice that for Aquinas love is found in every existing thing. It is present in each thing as a natural inclination toward its good. For Aquinas, it is not the case that love is something had only by God, angels, and humans, and is devoid from non-rational animals, plants, and inanimate objects. For Aquinas, the primary movement of anything that moves, is love. But love is present in a thing according to the nature of the thing. In other words, things with lower natures love in only a limited way compared with things that by nature have greater apprehensive power. This correlation of love and knowledge is based on the principle from St. Augustine that nothing is loved except it be first known (nihil amatur nisi cognitum). (ST I Q.60 a.1 s.c.) Thus the greater a thing's natural capacity for knowing, the greater its natural capacity for loving.

This principle, quite importantly, also works the other way around: the more we love something, the more we are able to know it. We become more observant about it, more interested in every detail about it, more likely to retain it in our memory, and more intent on understanding it in its entirety and to its core. Where our heart is, there our mind operates. This is how someone like St. Thérèse de Lisieux, whose heart was bursting with love for God, and who never went to seminary or graduate school, and who died at the age of 24, could become a doctor of the Church.

So although love requires knowledge, knowledge is advanced by love. A being's capacity for love is dependent upon its appetitive capacity, which in turn is dependent on its capacity for knowing. Elsewhere Aquinas distinguishes these three appetitive powers in a similar manner. He writes:

Love is something pertaining to the appetite; since good is the object of both. Wherefore love differs according to the difference of appetites. (Unde secundum differentiam appetitus est differentia amoris.) For there is an appetite which arises from an apprehension existing, not in the subject of the appetite, but in some other: and this is called the "natural appetite." Because natural things seek what is suitable to them according to their nature, by reason of an apprehension which is not in them, but in the Author of their nature, as stated in the [ST I Q.6 a.1 ad 2; ST I Q.103 a.1 ad. 1,3]. And there is another appetite arising from an apprehension in the subject of the appetite, but from necessity and not from free-will. Such is, in irrational animals, the "sensitive appetite," which, however, in man, has a certain share of liberty, in so far as it obeys reason. Again, there is another appetite following freely from an apprehension in the subject of the appetite. And this is the rational or intellectual appetite, which is called the "will." (ST I-II Q.26 a.1 co.)

Aquinas then continues:

Now in each of these appetites, the name "love" is given to the principle movement towards the end loved (principium motus tendentis in finem amatum). In the natural appetite the principle of this movement is the appetitive subject's connaturalness with the thing to which it tends, and may be called "natural love": ... In like manner the aptitude (coaptatio) of the sensitive appetite or of the will to some good, that is to say, its very complacency (complacentia) in good is called "sensitive love," or "intellectual" or "rational love." So that sensitive love is in the sensitive appetite, just as intellectual love is in the intellectual appetite. (ST II-I Q.26 a.1 co.)

In each of the three appetitive powers, there is a principle movement towards the end loved, and this is love.

But first let us ask what Aquinas means by connaturalness, aptitude, and complacency? Connaturality shouldn't be understood as a relation of mathematical forms, devoid of teleology. For Aquinas says, "But the true is in some things wherein good is not, as, for instance, in mathematics." (ST I Q.16 a.4 s.c.) And yet connaturality is a principle of motion. But nothing moves except insofar as it moves toward a perceived good. Therefore connaturality should not be understood as the relation of abstract forms such as those of mathematics. Connaturality is a kind of sharing of the same nature, in some respect. Thus in the encounter of that which is connatural to oneself, self-love is extended outward to the other, and rests in the other as it already rests in the self. (More on that later.)

Regarding love as the principle movement toward the end loved, Aquinas says the same elsewhere when he says, "love is the first movement of the will and of every appetitive faculty" (Primus enim motus voluntatis, et cuiuslibet appetitivae virtutis, est amor.) (ST I Q.20 a.1 co.) In that same place he explains in more detail what he means in saying that love is the first movement of the will and of every appetitive faculty. He writes:

Now there are certain acts of the will and appetite that regard good under some special condition, as joy and delight regard good present and possessed; whereas desire and hope regard good not as yet possessed. Love, however, regards good universally, whether possessed or not. Hence love is naturally the first act of the will and appetite; for which reason all the other appetite movements presuppose love, as their root and origin. For nobody desires anything nor rejoices in anything, except as a good that is loved: nor is anything an object of hate except as opposed to the object of love. Similarly, it is clear that sorrow, and other things like to it, must be referred to love as to their first principle. Hence, in whomsoever there is will and appetite, there must also be love: since if the first is wanting, all that follows is also wanting. (ST I Q.20 a.1 co.)

Love then, for Aquinas, is the principle movement of the will and appetite, not in the sense of being temporally prior (even if it is temporally prior), but in the sense of being formally and teleologically prior. Every other movement of the will and appetite presupposes love, and therefore these other movements formally and teleologically depend on love.

We can see already, however vaguely, that love is unitive by its very nature. Since love is the first movement of the will and appetite toward the end loved, therefore love by its very nature aims at union of the appetitive subject (i.e. the one having the appetite) with the end loved. In the next post in this series, I intend to write about the distinction between the love of concupiscence and the love of friendship.

In order to understand better why love seeks union with the beloved, we first need to step back and consider what love is. I am not here addressing the theological virtue of charity. Grace builds upon and perfects nature, so to understand the theological virtue of charity, we must first understand natural love. Writing about the nature of love may not seem to have anything to do with the reunion of all Christians. But it serves as the philosophical background for the argument that if we truly love one another, then we will actively be seeking unity with each other, pursuing every attempt to be reconciled and reunited. Part of what it means to obey Christ's command to love one another, I will argue, is to seek unity with each other. If we say that we love each other, but are content with being divided, then we are deceiving ourselves. A week ago Pope Benedict said, "Is it indeed possible to be in communion with the Lord if we are not in communion with each other? How can we present ourselves divided and far from each other at God's altar?" Some of what I have written in this post is more philosophical in nature and terminology, so please bear with me.

Aquinas tells us that everything by its very nature has a natural aptitude or inclination toward its natural form, that is, its natural perfection. In things that do not have knowledge, this natural aptitude is called natural appetite (appetitus naturalis). (ST I Q.19 a.1 co.) Seedlings, for example, have a natural appetite for becoming full-grown trees, even though seedlings do not themselves have knowledge of this goal. The knowledge of their goal remains in their Designer, but the natural appetite for their goal is within the seedlings.

Aquinas tells us that everything by its very nature has a natural aptitude or inclination toward its natural form, that is, its natural perfection. In things that do not have knowledge, this natural aptitude is called natural appetite (appetitus naturalis). (ST I Q.19 a.1 co.) Seedlings, for example, have a natural appetite for becoming full-grown trees, even though seedlings do not themselves have knowledge of this goal. The knowledge of their goal remains in their Designer, but the natural appetite for their goal is within the seedlings.In addition to this natural appetite, animals and humans have something that plants do not have; we have the power to sense material things that are outside of us. Accompanying this power to sense material things is an additional appetitive power by which we can desire the things whose sensible forms we receive in our sense powers. In virtue of this appetitive power, animals and humans can desire the things that we sense insofar as we apprehend them as desirable, i.e. as suited to our natural perfection. (ST I Q.78 a.1 co.) This appetite is the sensitive appetite or "sensuality" (sensualitas). (ST I Q.81 a.1 co.)

Humans are distinguished from other animals in that we have a rational soul. This allows us to receive not just sensible forms, but also intelligible forms. In this way we are capable of understanding what a thing is, that is, its essence. But again, along with this greater power of apprehension is a greater corresponding appetitive power. This greater appetitive power is the "rational appetite", which is another term for the will. Aquinas describes this three-fold distinction in appetites in this way:

[A]ll things in their own way are inclined by appetite towards good, but in different ways. Some are inclined to good by their natural inclination, without knowledge, as plants and inanimate bodies. Such inclination towards good is called "a natural appetite." Others, again, are inclined towards good, but with some knowledge; not that they know the aspect of goodness [rationem boni], but that they apprehend some particular good; as in the sense, which knows the sweet, the white, and so on. The inclination which follows this apprehension is called "a sensitive appetite." Other things, again, have an inclination towards good, but with a knowledge whereby they perceive the aspect of goodness [boni rationem]; this belongs to the intellect. This is most perfectly inclined towards what is good; not, indeed, as if it were merely guided by another towards some particular good only, like things devoid of knowledge, nor towards some particular good only, as things which have only sensitive knowledge, but as inclined towards good in general[universale bonum]. Such inclination is termed "will." (ST I Q.59 a.1 co.)

Aquinas sums this up in his answer to the question of whether there is natural love in the angels. And here we see what appetite has to do with love. He writes:

But it is common to every nature to have some inclination; and this is its natural appetite or love. This inclination is found to exist differently in different natures; but in each according to its mode. Consequently, in the intellectual nature there is to be found a natural inclination coming from the will; in the sensitive nature, according to the sensitive appetite; but in a nature devoid of knowledge, only according to the tendency of the nature to something. (ST I Q.60 a.1 co.)

Notice that for Aquinas love is found in every existing thing. It is present in each thing as a natural inclination toward its good. For Aquinas, it is not the case that love is something had only by God, angels, and humans, and is devoid from non-rational animals, plants, and inanimate objects. For Aquinas, the primary movement of anything that moves, is love. But love is present in a thing according to the nature of the thing. In other words, things with lower natures love in only a limited way compared with things that by nature have greater apprehensive power. This correlation of love and knowledge is based on the principle from St. Augustine that nothing is loved except it be first known (nihil amatur nisi cognitum). (ST I Q.60 a.1 s.c.) Thus the greater a thing's natural capacity for knowing, the greater its natural capacity for loving.

This principle, quite importantly, also works the other way around: the more we love something, the more we are able to know it. We become more observant about it, more interested in every detail about it, more likely to retain it in our memory, and more intent on understanding it in its entirety and to its core. Where our heart is, there our mind operates. This is how someone like St. Thérèse de Lisieux, whose heart was bursting with love for God, and who never went to seminary or graduate school, and who died at the age of 24, could become a doctor of the Church.

So although love requires knowledge, knowledge is advanced by love. A being's capacity for love is dependent upon its appetitive capacity, which in turn is dependent on its capacity for knowing. Elsewhere Aquinas distinguishes these three appetitive powers in a similar manner. He writes:

Love is something pertaining to the appetite; since good is the object of both. Wherefore love differs according to the difference of appetites. (Unde secundum differentiam appetitus est differentia amoris.) For there is an appetite which arises from an apprehension existing, not in the subject of the appetite, but in some other: and this is called the "natural appetite." Because natural things seek what is suitable to them according to their nature, by reason of an apprehension which is not in them, but in the Author of their nature, as stated in the [ST I Q.6 a.1 ad 2; ST I Q.103 a.1 ad. 1,3]. And there is another appetite arising from an apprehension in the subject of the appetite, but from necessity and not from free-will. Such is, in irrational animals, the "sensitive appetite," which, however, in man, has a certain share of liberty, in so far as it obeys reason. Again, there is another appetite following freely from an apprehension in the subject of the appetite. And this is the rational or intellectual appetite, which is called the "will." (ST I-II Q.26 a.1 co.)

Aquinas then continues:

Now in each of these appetites, the name "love" is given to the principle movement towards the end loved (principium motus tendentis in finem amatum). In the natural appetite the principle of this movement is the appetitive subject's connaturalness with the thing to which it tends, and may be called "natural love": ... In like manner the aptitude (coaptatio) of the sensitive appetite or of the will to some good, that is to say, its very complacency (complacentia) in good is called "sensitive love," or "intellectual" or "rational love." So that sensitive love is in the sensitive appetite, just as intellectual love is in the intellectual appetite. (ST II-I Q.26 a.1 co.)

In each of the three appetitive powers, there is a principle movement towards the end loved, and this is love.

But first let us ask what Aquinas means by connaturalness, aptitude, and complacency? Connaturality shouldn't be understood as a relation of mathematical forms, devoid of teleology. For Aquinas says, "But the true is in some things wherein good is not, as, for instance, in mathematics." (ST I Q.16 a.4 s.c.) And yet connaturality is a principle of motion. But nothing moves except insofar as it moves toward a perceived good. Therefore connaturality should not be understood as the relation of abstract forms such as those of mathematics. Connaturality is a kind of sharing of the same nature, in some respect. Thus in the encounter of that which is connatural to oneself, self-love is extended outward to the other, and rests in the other as it already rests in the self. (More on that later.)

Regarding love as the principle movement toward the end loved, Aquinas says the same elsewhere when he says, "love is the first movement of the will and of every appetitive faculty" (Primus enim motus voluntatis, et cuiuslibet appetitivae virtutis, est amor.) (ST I Q.20 a.1 co.) In that same place he explains in more detail what he means in saying that love is the first movement of the will and of every appetitive faculty. He writes:

Now there are certain acts of the will and appetite that regard good under some special condition, as joy and delight regard good present and possessed; whereas desire and hope regard good not as yet possessed. Love, however, regards good universally, whether possessed or not. Hence love is naturally the first act of the will and appetite; for which reason all the other appetite movements presuppose love, as their root and origin. For nobody desires anything nor rejoices in anything, except as a good that is loved: nor is anything an object of hate except as opposed to the object of love. Similarly, it is clear that sorrow, and other things like to it, must be referred to love as to their first principle. Hence, in whomsoever there is will and appetite, there must also be love: since if the first is wanting, all that follows is also wanting. (ST I Q.20 a.1 co.)

Love then, for Aquinas, is the principle movement of the will and appetite, not in the sense of being temporally prior (even if it is temporally prior), but in the sense of being formally and teleologically prior. Every other movement of the will and appetite presupposes love, and therefore these other movements formally and teleologically depend on love.

We can see already, however vaguely, that love is unitive by its very nature. Since love is the first movement of the will and appetite toward the end loved, therefore love by its very nature aims at union of the appetitive subject (i.e. the one having the appetite) with the end loved. In the next post in this series, I intend to write about the distinction between the love of concupiscence and the love of friendship.

Saturday, September 27, 2008

Congratulations Jonathan and Susan!

I've known Jonathan Deane for a little over three years. Those of you who regularly read my blog might recognize his name, because he has commented here quite often, especially last year. (He posts here as "contrarian 78", and his previous blog was titled "Contrarian Presbyterian".) In May of this year I linked to his post titled "The Stone Caster". He is very good at seeing into narratives, seeing implications and even counterfactual implications in them, and taking an accepted position and using a narrative illustration to show how that position is flawed.

So what's the news? He and his wife Susan are being received into full communion with the Catholic Church today. If you would like to congratulate them, stop over at Jonathan's blog, "Here you will find my mathoms" and leave a note.

So what's the news? He and his wife Susan are being received into full communion with the Catholic Church today. If you would like to congratulate them, stop over at Jonathan's blog, "Here you will find my mathoms" and leave a note.

Monsieur Vincent

Today is the feast day of St. Vincent de Paul, who died on this day in 1660. Just last week my wife and I watched the 1948 film "Monsieur Vincent", which is about the life of St. Vincent de Paul. (Clicking on the image above will take you to the Amazon page selling the DVD.) I recommend the film highly. It is understandable why this man is a saint. The entire passion of his life was to serve Jesus by caring for the poor. He saw the dignity of the image of God in every human person, especially in the sick, the weak, the helpless and the poor. His vision of Christ in the poor reminds me of the scene (linked to here) at the end of the film "Schindler's List", where Oskar Schindler finally realizes how valuable every person is in comparison to material goods. Steven Greydanus of Decent Film Guide, has a good review of Monsieur Vincent here.

Serving the poor is an activity in which Christians of all traditions can cooperate. It is easy to think that in our modern era, various social programs have all this covered. But Jesus tells us that in this age, the poor will always be with us. (St. Matthew 26:11, Mark 14:7, John 12:8) This is true even in wealthy societies such as our own. And it is especially true when the economy takes a downturn. How we treat the poor is one of the ways that Jesus will separate the sheep from the goats. (See St. Matthew 25) That's because how we treat the poor and the sick and the defenseless shows our heart; it shows whether we love Him whose image they bear.

Addendum: Here are two places to connect with others in serving the poor -- the Society of St. Vincent de Paul [USA], and Catholic Charities [USA].

Friday, September 26, 2008

Monocausalism and the Rock on which the Church is Built

From the Catholic point of view, Christ Himself is the cornerstone of the Church. Christ is one Person in two natures: one invisible, and one visible. So the Church (His Body) likewise has both aspects. It is both a visible organization and a spiritual community. (See CCC 771)

Although Christ is the head and chief cornerstone of the Church, during His absence [between the time of His ascension and the time of His return] He has entrusted the keys of His kingdom to His chief steward. (cf. Matthew 16:18-19, Luke 12:42) In other words, from a Catholic point of view, there is no contradiction between Christ being the head and cornerstone of the Church, and Peter also being a rock (subordinate to Christ) upon which Christ builds His Church, in the sense of making Peter its chief steward.

Often in Catholicism it is not an "either/or", but a "both/and". And the same is true of Matthew 16. But in Protestant contexts we quite commonly encounter the following dilemma: either the rock Jesus speaks of here is Peter or it is Peter's confession. But this is a *false* dilemma. The reason it is a false dilemma is that it is based on an implicit monocausalist assumption, i.e. that only one thing can be the rock on which the Church is built.

From a Catholic point of view there are at least four things the Church is built on: (1) Christ, who is the referent of Peter's confession of faith, (2) Peter the Rock, who makes the confession of faith, (3) the propositional content of Peter's confession, and (4) Peter's act of faith, for which He was commended by Christ, and given the keys by Christ. Each of these last three points to Christ. God the Father had revealed Christ's identity to Peter first, and this was a sign that Peter was to be the chief steward of the Kingdom, that is, the chief representative of Christ. The steward points to Christ because He is Christ's representative, the "vicar of Christ". The propositional content of Peter's confession obviously points to Christ, for Christ is what Peter's words were about. And Peter's act of faith points to Christ too, as an act of worship speaks about the worthiness of the recipient.

These last three are the three "bonds of unity" of the Church. (See CCC 815) I wrote about these in more detail under the section "The Three Modes of Organic Unity" here.

So the Catholic Church does not think it has to choose between Peter being the rock, and Peter's confession being the rock, and Peter's faith being the rock. They are all true, and they are all inseparable.

Here are some paragraphs from the Catholic Catechism that show how the Catholic Church views Peter's faith as the rock (even while, of course, believing that Peter himself is the rock).

"Moved by the grace of the Holy Spirit and drawn by the Father, we believe in Jesus and confess: 'You are the Christ, the Son of the living God. On the rock of this faith confessed by St. Peter, Christ built his Church." (CCC 424)

"Such is not the case for Simon Peter when he confesses Jesus as "the Christ, the Son of the living God", for Jesus responds solemnly: "Flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but my Father who is in heaven." Similarly Paul will write, regarding his conversion on the road to Damascus, "When he who had set me apart before I was born, and had called me through his grace, was pleased to reveal his Son to me, in order that I might preach him among the Gentiles..." "And in the synagogues immediately [Paul] proclaimed Jesus, saying, 'He is the Son of God.'" From the beginning this acknowledgment of Christ's divine sonship will be the center of the apostolic faith, first professed by Peter as the Church's foundation." (CCC 442)

"Simon Peter holds the first place in the college of the Twelve; Jesus entrusted a unique mission to him. Through a revelation from the Father, Peter had confessed: "You are the Christ, the Son of the living God." Our Lord then declared to him: "You are Peter, and on this rock I will build my Church, and the gates of Hades will not prevail against it." Christ, the "living Stone", thus assures his Church, built on Peter, of victory over the powers of death. Because of the faith he confessed Peter will remain the unshakable rock of the Church. His mission will be to keep this faith from every lapse and to strengthen his brothers in it." (CCC 552)

In contrast, Protestants tend to see the rock only as the content and/or act of faith in Peter's confession. They tend not to see the significance (with respect to office) in Christ changing Simon's name to Peter and giving him the keys of the kingdom. They tend to read Matthew 18:18 as nullifying any uniqueness in Peter's office shown by Christ giving him the keys.

I have distinguished previously (here and here) between "comparing form" vs. "tracing matter". Here I'm pointing out that the Catholic Church believes that the Petrine office has preserved the faith of the Apostles, and that this is part of the significance of Matthew 16 -- Peter's being made a rock by Christ and being given the keys of the kingdom, and later being charged with feeding Christ's sheep and strengthening the faith of his brothers (the other Apostles) in John 21 and Luke 22. The Church believes that this matter (this office) has been given the keys, so as to preserve the form (i.e. the deposit of faith in its propositional and dynamic aspects) that was entrusted to it. The Church believes that the form and matter always remain united, just as the visible and invisible are held together in Christ's hypostatic union.

Thursday, September 25, 2008

St. John 6:63

"τὸ πνεῦμά ἐστιν τὸ ζῳοποιοῦν, ἡ σὰρξ οὐκ ὠφελεῖ οὐδέν: τὰ ῥήματα ἃ ἐγὼ λελάληκα ὑμῖν πνεῦμά ἐστιν καὶ ζωή ἐστιν."

"The Spirit is the one making alive, the flesh does not help at all. The words that I have spoken to you are Spirit and are Life."

Some people use John 6:63 to claim that Jesus did not really mean (in John 6:27-58) that we must actually eat His flesh and drink His blood. They say, "See, it is the Spirit that is important; the flesh doesn't help at all. Jesus doesn't think that we are saved by matter. What is important is that we have faith and believe in Him. He even says here that His words are Spirit and Life. That's what we should 'eat', His words. He doesn't mean that we need to eat His Body and drink His Blood in order to have eternal life, but simply to believe the words that He said, and believe in Him. This verse shows, they argue, that eating His Body and drinking His blood just means that we are to believe His words, by the work of His Spirit in our hearts. We are saved by faith alone, not by matter."

But this is a misunderstanding of John 6:63. In order to understand John 6:63 rightly, we have to keep 6:26 in mind. That verse says, "Jesus answered them and said, "Truly, truly, I say to you, you seek Me, not because you saw signs, because because you ate of the loaves, and were filled." The people were seeking Jesus because of the flesh, not the Spirit. That is, they wanted their bellies filled with more bread and fish. In John 6:63 Jesus is not saying that His flesh profits nothing. That would directly contradict everything He just said. He is saying that being led by our flesh [i.e. our bellies, the fleshly desires for the temporal things of this world] profits nothing. We cannot find true life that way. That is what Jesus had said in John 3:6 to Nicodemus, "That which is born of the flesh is flesh; and that which is born of the Spirit is spirit." True life comes by the work of the Holy Spirit, who opens our eyes and hearts to the things of the Spirit. The same sense of the term 'flesh' is used in John 8:15, where Jesus says, "You people judge according to the flesh."

We see this distinction [between what is of the flesh, and what is of the Spirit] even among the Twelve, in John 6:66-71, where John contrasts Peter and Judas. (Recall that Matthew tells us that Jesus said of Peter, "Flesh and blood has not revealed this to you" - Matthew 16:17.) We also see this same distinction in John 6:36-40, where Jesus is contrasting those who are given to Him by the Father with those who do not have faith. Those who do not have faith are still 'in the flesh'. We see this distinction again in John 6:44. Jesus is contrasting those who have faith, and believe in Him, with those who have the old covenant but do not have faith in Christ, who fulfills the old covenant.

So there are two distinct points being made here in this part of John 6. One is that if a person is merely in the flesh, and has not been given new life by the Spirit so as to believe in Christ, he cannot understand the things of the Spirit. The second point is that Christ Himself is the Bread of Life, such that if any man eats His flesh and drinks His blood, that man has eternal life. But that second point is only open [epistemically] to people who are not "in the flesh", that is, those who are not just following their carnal appetites, void of the Spirit. Unless a man is born again by the Spirit, what Christ says about Himself being the Bread of Life and people eating His flesh and drinking His blood becomes a stumbling block. (John 6:61) But if the Spirit quickens a man in his spirit, then he does not stumble over the "difficult statement" Jesus has given earlier in the chapter about "eating my flesh and drinking my blood".

In Romans 8:5 Paul writes,

"For those who are according to the flesh set their minds on the things of the flesh, but those who are according to the Spirit, the things of the Spirit."

And then in Romans 8:9 he writes, "So then they that are in the flesh cannot please God."

In fact, the first part of Romans 8 is all about this distinction. Similarly, in 1 Corinthians 2:14, Paul writes,

"But a natural man does not accept the things of the Spirit of God, for they are foolishness to him; and he cannot understand them, because they are spiritually appraised."

That is the idea that Jesus is communicating in the first part of John 6:63. He is not saying that His own flesh and blood does not give Life. He is saying that the Spirit opens a man to understand by faith how what Jesus has been saying about eating His flesh and drinking His blood is possible in the holy sacrament of the Eucharist. It makes no sense to the man without the Spirit, and is thus a cause of stumbling to those who do not see with the eyes of faith, given by the Spirit.

In John 6:62, He is saying, If you are already stumbling over my telling you that you have to eat my flesh and drink my blood, then how will you make sense of that when you see me ascend into heaven? His disciples, apparently, had been thinking that Jesus would cut Himself up into pieces, and give pieces of His body to them to eat. But they were still thinking carnally, not understanding that Jesus was not talking about cutting off pieces of His body, but rather about giving His body and blood to them sacramentally in the Eucharist, which He had yet to institute on the night in which He was betrayed.

In the second half of John 6:63, when Jesus says, "the words that I have spoken to you are Spirit and Life", He is saying both that the meaning of His words is made known to us only by the Spirit, and that by abiding in His words (i.e. believing and obeying them, i.e. continuing in the Eucharist, and not separating ourselves from the Body of Christ) we remain in the Spirit and in the Life of Christ.

Tuesday, September 23, 2008

Stigmata: From God or not?

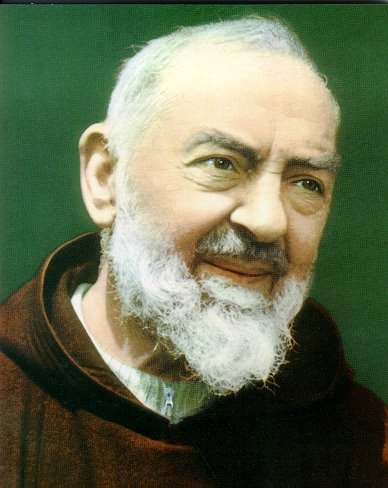

Today is the feast day of St. Pio of Pietrelcina (known as Padre Pio). He is a modern day Catholic saint who died at 2:30 AM on this day in 1968. His life is quite amazing, and the stories told about him are remarkable. The most amazing thing about him is that he bore the stigmata (the five wounds of Christ; cf. Galatians 6:17) for 50 years. More information has recently been released about his stigmata here. I wrote a bit more about him last year here.

The Catholic encyclopedia article on mystical stigmata is here. St. Francis of Assisi received the stigmata on the feast of the Exaltation of the Cross (September 14) in the year 1224.

According to the Catholic encyclopedia article, there have been over three hundred persons who have received the stigmata. So far as I know, they have all been Catholic. So, are stigmata from God or not? If stigmata are not from God, then why were men like St. Francis and St. Pio such holy men? But if stigmata are from God, then why do Catholics receive them but Protestants do not?

Sunday, September 21, 2008

Babel or Keys?

Hendrick III van Cleve (1525 - 1589)

(click on the painting to view it full-sized)

Christ promised that the gates of hell would not prevail against the Church. But the very nature of the promise implies the presence of a war. The dragon "makes war" against the children of Christ's Mother, that is, those who "keep the commandments of God and hold to the testimony of Jesus." (Rev 12:17) So how does hell fight against Christ's Church? Of course there are external threats, such as persecution and the enticement of worldliness. But the more insidious attacks are internal; these are heresy and schism. Heresy and schism generally go together, because one without the other would be exposed for what it is. Only together can they hide each other. Satan hides himself in a certain respect, disguising himself as an angel of light. (2 Cor 11:14) That is his standard mode of operation. He once was Lucifer, the light bearer. So he portrays all his works as good and right and enlightened, as though they are the path of the truly wise, and especially suitable for making one wise. This is how he deceived Eve. This is how he deceived the people into choosing the murderer Barabbas [whose name means "son of the father"] over the innocent Son of God. And this is how he continues to deceive people into sinning against the Body of Christ, by leading them into heresy and schism.

But evil is always intrinsically self-destructive, because not only is evil a privation of good, but evil is also therefore a privation of unity and a privation of being. That is why evil is always parasitic on the good. Evil cannot exist on its own, but only in and in relation to what is good. For this very reason, the concepts of heresy and schism are not themselves sustainable within heresies and schisms. Within heresies and schisms these concepts collapse into the semantic equivalent of 'disagreement with my interpretation' and 'separation from me', respectively. All their objectivity and normativity is lost. Just as Satan succeeds when people no longer believe that he exists, so also he succeeds when the concepts of 'heresy' and 'schism' have been so evacuated that people no longer believe there really are such things.

The Church is supposed to be the voice of Christ to the world. Satan cannot defeat this voice, but through heresies and schisms he can drown it out in a sea of competing voices, each claiming to speak for Christ. In this way he creates confusion, not only in the world but even among Christians, for the effect is as if there is no authoritative voice of Christ, but merely a cacophony of opinions. Yet "God is not a God of confusion". (1 Cor 14:33) Christ did not leave His sheep without a shepherd. Nor did he intend that all who wish to determine who is the true shepherd first learn to read, let alone read and exegete Greek and Hebrew (as is testified to by the theological disunity among those who *do* read and exegete Greek and Hebrew).

The schisms that have weakened the unity and strength of our voice as Christians are in their effect like the curse of Babel that thwarted the builders of that tower. But the purpose of the coming of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost is to reverse that division by means of a divine ingathering. This was the significance of the gift of tongues on the day of Pentecost, as described in Acts 2. (See the column of paintings on Neal Judisch's blog to get a better sense of the idea.) Babel was the tower of man, initiated by men and built up by men. It is the paradigmatic referent of Psalm 127:1, "Unless the LORD builds the house, its builders labor in vain". Nimrod is said to have been the initiator of the tower of Babel; in this way he is a figure of the Antichrist. In contrast to Babel, the Church is the tower that God is building, joining all peoples together into one Body in which we all speak the same divine language. (To read an early second century description of the Church as the tower that God is building, see Book 1 of the Shepherd of Hermas.) This is the Body of Christ, of which He is the founder and Head.

One way to respond to the common insouciance among Christians regarding our disunity is to show the disunity for what it is, as Dickens showed child labor for what it was. That is the sort of thing I was attempting to do recently here and here, in showing that the position of those Protestants who claim to believe in a visible Church is only *semantically* distinct from the position of those Protestants who deny that there is a visible Church. This highlights the absence of a middle position between Catholicism on the one hand, and that of those who deny that Christ founded a visible Church. The denial of a visible Church leaves each man to do what is right in his own eyes, for in that case there is no divinely-established voice of authority in the visible Church, because there is no visible Church. This position has difficulty making sense of St. Matthew 16 and St. Matthew 18, as I showed in the comments here.

Moreover, the ecclesiological position of those who deny that Christ founded a visible Church is intrinsically disposed to perpetual fragmentation and disharmony and weakness, for according to that position Christ did not establish a lasting hierarchy by which to preserve and guard the first mark of the Church: unity. But while Christ assured us that the Church will endure, He also tells us that a house divided cannot stand (St. Matt 12:25; St. Mark 3:25; St. Luke 11:17). Therefore, unity is an essential mark of the Church. Christ did not tell us to make a man-made peace that He would then preserve. He gave to His Apostles His peace, a peace that is not of this world. He left His peace with them. (St. John 14:27; Philippians 4:7) This is the divine peace and unity into which we must be incorporated. It is this divine peace and unity given by Christ to the Church that makes unity the first mark of the Church.

There are many Christians who recognize the need for greater unity among Christians. The moral decline in the broader culture makes such a need more and more obvious. And the recognition of this need for greater unity should be commended and encouraged, as should the efforts to effect it. But there are two fundamentally different types of ecumenicism. St. Thomas Aquinas tells us the goal of a thing shows us what it is, and the difference in goal distinguishes these two different types of ecumenicism. I'm not speaking here of the proximate goal of fostering dialogue and improving mutual understanding and social cooperation between Christians of various denominations and traditions. I'm speaking of the final goal.

I have written here about the way in which one form of ecumenicism unwittingly continues the work of Babel, by trying to create a new tower that Christ Himself did not found. It does this by seeking to establish a new institution and trying to get all Christians to be united to it. We see this mentality in organizations like the World Council of Churches, the National Council of Churches and the World Alliance of Reformed Churches. (For an example, see here.)

True ecumenicism does not lay a new foundation other than that which God has already laid, the incarnate Christ being the cornerstone, followed by the "apostles and prophets" (Eph 2:20), and their successors in the Church, which is "the pillar and foundation of the truth" (1 Tim 3:15). True ecumenicism is therefore necessarily by its very nature and final goal a searching for and reuniting with the Church that Christ founded. So long as some Christians conceive of the Church that Christ founded as the mere set of all believers, or as the set of all believers and their activities, or as a mere phenomenon, they will not perceive what the Church actually is, and how the Church is the pillar and foundation of the truth. Mere sets and mere phenomena have no authority, no actual unity, and thus no actual being. What has no being cannot be a foundation, let alone a foundation of the truth.

To defeat the divisive work of Satan, we first have to come to see schisms for what they are. This is part of what it means to expose the works of darkness. (Eph 5:11) We tear away the façade of light that keeps us from perceiving evil as evil. These schisms are "ruptures that wound the unity of Christ's Body" (CCC 817). If we love our own bodies, then how much more should we care for the wounds of Christ's Body? But we can go about seeking to heal these wounds in one of two ways. We can either take the keys to ourselves, which is the way of Babel (or more precisely, an endless series of Babels, each with its own self-appointed or de facto Nimrod), or we can seek out the Church that Christ founded, where He left His peace, seeking full communion with the one to whom He gave the keys.

Thursday, September 18, 2008

Love and Unity: Part 1

This is the first of a series of posts on the relation between love and unity, as I mentioned in early August that I intended to write. At a later time I hope to write about the relation between love and truth. But for now I want to focus on how and why love seeks unity with the beloved, and the way in which unity with the beloved constitutes love. I have written about this relation previously here and here. I was again prompted to write about this subject earlier this year, as I reflected on the nature of love, and also as I experienced the conjunctive dissonance of stated love and simultaneous contentment with disunity.

The experience was similar to the dissonance described in St. James 2:14-26 between the simultaneous presence of stated faith and the absence of charity. St. James calls such a faith "dead faith". Likewise, in reflecting on the nature of love I concluded that contentment with disunity, all other things being equal, is something like "dead love". True [living] love tirelessly seeks union with the beloved, and does not rest content with disunity. That pursuit of unity may take different forms, depending on various other factors. But if a man says that he has love for his brother, but is content with disunity, he is deceiving himself. If he says to his brother, "Go in peace, with all my love", but does not seek out reconciliation (St. Matthew 5:24) and resolution of the schism that divides him from his brother, he does not truly love. True love seeks both to reach over and break down the wall of separation, even if that activity involves immense sacrifice, suffering, rejection, and persecution -- even if it involves the cross.